|

"Sport" is a cultural field of activity in

which people voluntarily enter into a relationship with other

people in order to compare their respective abilities and skills

in the art of movement - according to self-imposed or adopted

rules and on the basis of socially accepted ethical

values.

"Sport" ist ein kulturelles

Tätigkeitsfeld, in dem Menschen sich freiwillig in eine

Beziehung zu anderen Menschen begeben, um ihre jeweiligen

Fähigkeiten und Fertigkeiten in der Bewegungskunst zu

vergleichen - nach selbst gesetzten oder übernommenen Regeln

und auf der Grundlage der gesellschaftlich akzeptierten ethischen

Werte.

"Sport" est un domaine

d'activité culturel, dans lequel les gens s'engagent

volontairement dans une relation avec d'autres personnes afin de

comparer leurs capacités et compétences respectives

dans l'exercice physique adroit - selons des règles

autoétablies ou héréditaires et sur la base

de valeurs éthiques socialement

acceptées.

My German definition of "Sport" was first put on the

Internet in January 2002 and has been revised several times since

then. The here presented English version is simply a proposal,

too, which I would like to put up for discussion.

In the following, I will first explain why and how I define "sport", secondly I will

discuss the limits and benefits of my

proposed definition, and thirdly I will explain the individual elements of my

definition.

1. Define "sport" - why and

how?

To define "sport" (in English) is a big task,

especially for me, a German. My efforts are based on my (German) definition of

the German term "Sport" (explaned).

In (American) English, furthermore, there is a fine

distinction between "sport" and "sports". The editors of the

"Routledge Companion to Sports History" (Abingdon & New York,

2010), S. W. Pope and John Nauright, addressed this issue in

their first footnote (p. 9) with resigned regret: "Both of us

(like most historians in our field) have consistently referred to

our work as 'sport history' which somehow seemed a bit more

serious than 'sports history'. Routledge preferred 'sports

history' ..." - why at all?!

For me, it’s not only a "snobbish" attitude

or "a bit more serious" (Pope and Nauright, ibid. p. 9) to use

the term "sport" in the singular, but a question of the proper

linguistical category. "Sport" (in German: "Sport") in general

sense is an abstract term for a field of activity, and in this

sense it's (in German) a singulare tantum; you can use

it only in the singular. In English, "a (certain) sport" is a

special kind of activity, one of many (in German: "Sportart"); in

this sense, you can use it (in English) as well in the singular

as in the plural. So when you say "sports", it is

always a number of kinds of (sporting) activities.

The rare reflections on the term "Sport" by German

authors mostly remain vague and unprecise. They find their

culmination in Röthig's and Prohl's definition of "Sport" -

or better: its avoidance - in the (German) "sport-scientific

dictionary" ("Sportwissenschaftliches Lexikon", 2003, p. 493):

"Since the beginning of the 20th century, S. has developed

into a colloquial term used worldwide. Therefore, a precise or

even unambiguous conceptual delimitation cannot be made."

(my translation, C.T.). In the core statement, it has been in the

"Sportwissenschaftliches Lexikon" since 1983. This capitulation

to the necessary conceptual effort or even the explanation that

it is from the outset not a meaningful undertaking because it is

impossible, I consider a momentous step of thought, which in my

opinion has negatively determined the German publications of the

last decades.

In my opinion, every scientist must have as

clear a concept as possible of the subject of his science and

explain it in his publications. The idea that a

physicist does not have an exact concept of physics, a lawyer

does not have an exact concept of law, etc., might seem strange

to all people. But this is exactly what most and most influential

sport scientists in Germany (and also some in other countries and

cultures) declare to be normal or even normative.

The result are scientific works in which everything

is counted as "sport", even something as in my opinion absurd as

"health sport". In connection with the fact that

according to the prevailing view (represented in the

"Sportwissenschaftliches Lexikon") most sport scientists

do not even strive for a clear terminology, this results

in complete arbitrariness and ambiguity in the discourse of sport

science.

Anyone who is not willing to accept this

development (or this prevailing state in the meantime) must face

the laborious task of clarifying "sport" (as the central concept

of sport science); he/she must determine its scope or limits, and

that means defining "sport". And such a (working) definition must

be made public by every scientist. I am doing this hoping that

all those who strive for clear concepts in cultural studies will

give a productive resonance.

(Cf. the later mentioned and quoted definition of

"Bewegungskultur" [culture of human motion] as well

as my further proposed definitions of "Kunst" [art],

"Gewalt"

[violence], "Aggression" [aggression], as well as "Olympismus"

[olympism] and "Frieden" [peace], all of them at present

still only in German - sorry!)

A definition should determine and

delimit the meaning of a term. For the sake of clarification: To

understand a definition as a precept, regulation or the like

would be a misunderstanding. Every thinking person forms his/her

own opinion and uses words in his/her own meaning. But one should

not exaggerate this subjectivistically or constructivistically.

We are social beings, designed for exchange and understanding

with other people, in science in any case. If we want to

communicate with other people, who have their own use of words,

we must - even in a not completely unimportant everyday

conversation - be able to clarify our (respective) use of words,

at least on request.

Furthermore, scientists have to clarify their key

concepts from the outset, without waiting for demand. When sport

scientists unaskedly tell themselves and the interested public

what they understand by sport and why they use this term this

way, they only do what is necessary; if they don't, it's a

serious obstacle to understanding. In this sense,

defining is a necessary input for the scientific exchange

of knowledge and opinions.

Of course, definitions are not instruments that

should or could change reality in the first place; rather, it is

mainly the found (objectively given) reality in them that should

be brought into the (subjective) concept in a clear and selective

way. "in the first place", "mainly" - with this choice of words I

have already indicated that in all words, thus also (or even

more) in definitions, an idea of what reality could be (or

should be for me) is represented. This is what makes

subjectivity unbreakable.

With my words (and thus also definitions) I do not

pursue a purely objectivist ideal (which is not achievable

anyway). On the other hand, I don't understand my wording as

merely subjectivist, voluntaristic or even constructivistic. This

means that I accept the priority indicated above, in which both

are abolished: Definitions should be as clear and

selective as possible and at the same time at least indicate in

all fineness how reality could (or should)

be.

Several types of definitions can be distinguished:

Real (or essence) definition, nominal definition, declarative

definition, ostentatious and operational definition. I propose -

according to a philosophical tradition going back to Aristotle -

a so-called real definition. It should determine

the essence of the entity to be defined by indicating the next

higher genus (genus proximum) and the species-forming

difference (differentia specifica). Mistakes can be made

in a proper definition if, for example, it is too narrow or too

wide, contains contradictions, is unclearly formulated, contains

a negative formulation or even the word to be defined itself

(cf. Regenbogen, Arnim; Uwe Meyer (Eds.) (2013):

Wörterbuch der philosophischen Begriffe, founded by F.

Kirchner and C. Michaëlis, continued by J. Hoffmeister,

completely new ed. by A.R. und U.M. Hamburg: Felix Meiner 2013 (=

Philosophische Bibliothek, vol. 500), keyword

„Definition“).

If one wants to work out such a definition, as it

is offered by the way in most dictionaries and encyclopedias, one

must think first of all therefore, to which

genus (i.e. taxonomic group) sport belongs,

which terms are settled on the same level and which is the

next higher genus (term level, genus

proximum). To assign the term apple, for example, to the

genus fruit would go one step too far, because pome fruit is the

next higher genus. For me, the next higher genus for the

term "sport" is "field of activity". Sport is one of

many fields of activity for me. I have already somewhat limited

the abundance of fields of activity by the adjective "cultural".

I will explain this element of my definition and all others in

more detail below (point 3).

In the second step one has to name the

"species-forming difference" (differentia

specifica), i.e. what distinguishes the (cultural) field of

activity sport from other (cultural) fields of activity. This

should be formulated as succinctly and clearly as possible with

words or terms that are as generally understandable as possible.

From the fundamental necessity that the terms used here must be

defined again, some authors conclude that such an approach were

infinite or even circular, which were a serious violation of the

definition rules; therefore one could or should not even try

such. This concern is as puristic as it is infertile. In my

opinion, it is both sufficient and necessary to accept the indeed

logically conceivable circularity as a "blur" in order

to acquire a great gain in conceptual clarity in

practice.

It is clear that this definition is also

subjective, the result of (my) action and (my) decision.

This subjectivity is inescapable. Others will act and

decide, formulate and define differently. Science consists of

dealing with other subjects, their actions and decisions.

Scientists offer in principle and publicly to justify their own

actions and decisions in a comprehensible way and thus to make

them verifiable. And other scientists are confronted critically

with the same claim.

When Röthig and Prohl in the

"Sportwissenschaftliches Lexikon" claim that "therefore" "a

precise or even unambiguous conceptual delimitation" of "sport"

were not possible, they refuse to accept what (sport) science

fundamentally constitutes; they thus remain in everyday language

use - and with them already more than a generation of (esp.

German) sport scientists.

By the way: the (logical) conclusion, claimed by

the word "therefore", is inadmissible; because from the

(appropriately named) conceptual properties "colloquial" and

"used worldwide" it cannot (simply) be concluded that the term

"sport" cannot be defined "precisely or even unambiguously".

All elements of my definition of sport are

necessary, and only together they are sufficient. This

means that an activity no longer belongs to "sport" even if only

one of the defining elements is not given. This is a figure of

thought, which makes possible a clear demarcation, and that is

finally the literal sense of ‘defining’.

2. Limits and benefits of this sport

definition

My proposed definition only covers part of

the everyday and colloquial term "sport". According to

this, much can no longer be referred to as sport (at least in

scientific wording), that is called so in everyday language use

(e.g. "health sport"). The difference is indeed considerable!

In many discussions I have learned that many people

are reluctant to use the word "sport" in this (narrow) meaning.

This is probably not only a clinging to the usual, it is probably

above all defending against a feared "attack" on a meanwhile

socially deeply anchored value consciousness: Sport and/or

sportiness is felt by most people of our society as a high value

and is emotionally deeply anchored as such; this applies probably

all the more to most sport scientists. In the eyes (or "hearts"!)

of many, a much narrower concept of sport seems to query a part

of their lifestyle that they (want to) understand as

"sporty".

The conceptual change proposed by me may - at least

in the beginning - lead to considerable uncertainty. My proposal

to use the term "culture of movement" (in German:

"Bewegungskultur") as a wider generic term for the activities

which, according to my definition, can no longer be classified

under "sport", does not seem to be able to simply compensate for

the "loss of sportiness" which is perceived as emotionally

significant by many.

In my opinion, the greatest and most general

benefit of this conceptual clarification arises for the discourse

of sport science: If sport scientists know from each

other what they understand by "sport", they can - especially with

different views - talk to each other in clear awareness of their

(different) use of the central concept of their science. The

prerequisite for this, of course, is that each one has his/her

own concept of sport (elaborated and communicated).

By the way: The colleagues who pleaded for a change

of term from "sport" to "movement" science have thus (apparently)

avoided the necessity of defining "sport" as the central concept

of their science, but they have considerably increased their

problem. An immense number of isues has to do with movement! I am

astonished at all that representatives of philosophy, physics,

sociology, psychology or many other fields of science have not

already protested against the claim that (former) sport

scientists have made already some time ago to be the (very and

only) scientists of "movement" - especially in the challenging

singular "movement science". After all, movement is a very

complex concept and central in many fields of science!

To work out my "own" definition of "sport" seemed

to me necessary already for a long time due to general scientific

theoretical considerations. However, I only made a real attempt

when I was preoccupied with preliminary considerations on an

overall presentation of sport history. I had to clarify the

conceptual question more seriously than before: What exactly did

I mean by "sport"?

In publications on sport history, I had noticed for

a long time before that many authors - mostly in the prefaces -

have great difficulty "applying" the term sport to earlier times;

I call this the anachronism syndrome. They mostly

justified their concerns with today's broad use of the term

sport, which includes many earlier not existing practices. Thus

they entered a conceptual "dead end"; for with what words should

they name the phenomena of that time? And don't further

conceptual concerns emerge then?

I can only avoid this conceptual dilemma by

checking whether I can speak (and write) about "sport" both in

the present and in the past. This in turn requires a clear

definition.

With my definition, I have found

what I consider to be a useful solution. The definition

originated from the investigation of the present times and

circumstances, but due to its general formulation one can

also grasp the essence of what (of course from a today's

point of view) can be called "sport" in the distant

past.

In order to fill the big gap between my narrow

concept of sport and the boundless concept of sport, which is

used in everyday life and unfortunately also by most sport

scientists, I propose to use a word with a larger scope of

meaning: "culture of movement". Therefore I will speak of

"culture of movement and sport" in the future, if I want to grasp

the area of today's everyday term "sport". I have also

published and explained a proposal for the definition of the term

"culture

of movement" ("Bewegungskultur") on the Internet with

explanations, too:

"Movement culture" is a field of activity

in which people deal with their nature and environment and

consciously and intentionally develop, design and present their

physical abilities and skills in order to experience an

individual or shared gain and enjoyment that is important to

them.

If you use "sport" and "culture of movement" as

terms like I suggest, it is unimportant when and how these words

have been used so far; because with my definition I explain how I

want to use a word now (and in the future), what it means for me

here and now.

In my opinion, the much-discussed terminological

concerns of sports historians (I call it the anachronism

syndrome, which particularly affects authors researching ancient

sport history) are based on the fact that these authors have not

been able (or have been afraid) to clarify the meaning of the

term "sport" (by a definition). But if one faces this -

admittedly difficult - task, such concerns can be overcome. Some

(especially US-) authors (such as Mandell, Poliakoff and

Guttmann) have shown this in their (different) ways. The

usefulness of any definition can (and should) of course be argued

about - with a scientific claim.

In my opinion, the clearest proposal for a

definition of "sport" so far has been presented by the German

Meinhard Volkamer (1984): "Sport consists in the creation of

arbitrary obstacles, problems or conflicts, which are

predominantly solved by physical means, whereby the participants

agree on which solutions are to be allowed or not allowed" (my

translation, C.T.). It seems strange to me that Volkamer, in his

1987 version, removed the binding to agreed rules from his

proposed definition.

A (rare) example for the discussion hopefully to be

continued about a sport concept (especially for sport historians)

is the controversy in the first issue of the journal "Sport und

Gesellschaft - Sport and Society" of 2004 between Christiane

Eisenberg and Michael Krüger, in which Eisenberg - in my

opinion rightly - reproached Krüger (representing most other

German sport historians and scientists) for not (having and)

using a clear sport concept. By proposing a definition (which I

do not share), she has at least promoted the scientific

discussion, which has so far been culpably neglected.

3. Explanation of the individual

elements of my "sport" definition

For clarification, I will briefly explain the

individual elements of my definition of "sport" below:

"field of activity": This is the

"genus proximum" for the term "sport". Field of

activity (not: activity!) should clarify that "sport" is an

abstract issue, not an object, condition or the like. "Sport" is

also not a term for an activity, but a generic term (a field) for

many activities. Swimming, running or sailing are not from the

outset sports, but are words for certain activities, which -

only in a certain form! - belong to the (cultural) field

of activity called sport. In another form they can also

be words for everyday activities; then they belong to the field

of activity called everyday life.

If one wants to name an activity, one must use a

verb. Unfortunately, in German we do not have a simple one (such

as "sporten"), but only a compound one: "Sport treiben" generally

refers to activities in the field of sport (= sporting

activities). By the way, the composition of the words "Sport

treiben" also makes it clear that "Sport" in German is an

abstract term that needs a verb to name the activity in this

field. In English it seems similar: there is no single verb (like

"to sport") but the compound (like "to make sport").

The fact that the acting ones are humans (e.g. not

animals) seems to me self-evident, but must nevertheless be

clearly formulated; there are authors who advocate the thesis

that animals also practised "sport" (or "physical exercises",

Neuendorff 1930; Weiler also argues similarly in 1989). This will

hopefully become clearer with the following explanation of

"cultural".

"Field of activity" also means that the people in

this field do something themselves, act actively, in connection

with the other elements of this definition. People who, for

example, merely watch other sportsmen and sportswomen therefore

do not act in the field of sport, but in other fields of

activity, which, however, can be brought into connection

with sport. (Rioting) football "fans" are for me therefore

not necessarily a topic for sport scientists, but first and

foremost one for psychologists, sociologists or the like.

"Cultural": On the basis of the

natural circumstances and conditions, which humans have

influenced and changed (and still do) to an increasing extent,

people develop their ways of life culturally / socially. In the

tribal history of "homo", the ability to (self-)reflect means a

decisive step towards the development of communication, language

and free, playful thinking. Only after this development step can

one speak of "sport" (and other cultural fields of activity such

as "art"). Culture is the conscious, reflected shaping of

one's own development, both at the level of the human species and

at the level of the individual human being.

The cultural characteristic of sport becomes

particularly clear in the development of the sport rules (see

below!); people have thought about how they want to and can

shape the militant comparison with other people in such a way

that it could, for example, develop from bloody seriousness (as

it is partly described in the 23rd song of Homer's Iliad) to a

playful fight for higher art of movement.

The cultural quality of sport is not "proven" by

the fact that people in other cultural fields of activity - such

as fine arts or literature - have dealt with sport. This (wrong)

line of thought was (and still is) a popular element of public

speeches, but remains misleading as an attempt to enhance sport

as a relatively new cultural field with the consecration of

already recognised "elder" cultural areas. Such dubious figures

of thought are rather harmful, they are above all not necessary

at all.

"Voluntary": This criterion

excludes those people who act under pressure or coercion, even if

their activity otherwise fulfils all other criteria for sport,

e.g. most gladiators in Roman arenas (see below the remarks

on "on the basis of socially accepted ethical values"!).

Voluntariness should not be confused with joy,

pleasure or similar, by the way! The currently (in German)

so-called "Schulsport" (school sport), for example, although it

may be experienced by many as joyful, does not belong to sport

for me, insofar as it is part of compulsory education (compulsory

schooling, legal constraint!), i.e. it is not practised

voluntarily (up to a certain age). The former German term

"Leibeserziehung" ("physical education") was more honest.

Even in the "Bundeswehr" (army) and other closed

institutions one should not speak of "official sport", because

this activity is part of the service, i.e. not voluntarily

exercised; fitness training would be more appropriate; even more

honest would probably be the terms combat training or (para-)

military training, if forms of movement are practiced with

weapons.

Outside of school lessons, military service, etc.,

the same people can, of course, do sport(s), just voluntarily;

but within such coercive systems one should renounce this a label

fraud. For me, compulsory sport is a contradiction in terms.

Under the (actual) conditions of "professionalism",

athletes can (or must) gradually give up or lose the

voluntariness they may have experienced in the beginning. The

so-called "professional sport" functions to a large extent like a

coercive system, from which people cannot at least simply and

easily "get out". These circumstances sometimes suggest the (in

my eyes correct) statement: "This is not a sport (anymore)"! Also

the frequent comparison (or more precisely: the equation) of

today's professional athletes with antique gladiators has its

(limited) justification in this.

"to enter into a relationship with other

people": A single person without a relationship to

others is (already biologically) hardly viable. Social-cultural

life without human relationships would be a contradiction in

terms. Beyond this (banal) basic insight, an activity to be

called "sportive" is only justified by the fact that a human

being in this field of activity enters into a special,

comparative relationship (see below the remarks to

"compare"!) with at least one other human being through

his/her acting so.

Comparative relationship means for me that it is

valid only for humans among themselves as basically same beings.

No person can compare himself/herself with a mountain, for

example, even if colloquially "the mountain" is called an

(athletic?!) "opponent", even by otherwise serious sport

scientists (such as Güldenpfennig). For me this is not a

"relationship" (to a human being), but a "relation" (to a

thing).

Who only trains and compares his own physical

(movement) performance with the goal of surpassing it as much as

possible, has no relationship with an other person. This is of

course legitimate, but he/she does not make sport in my sense,

but rather culture of movement: Such a person deals with his/her

nature (and environment) and consciously develops his/her

physical abilities and skills in order to experience a

significant gain and pleasure for him/her. This corresponds

exactly to my definition of "culture of movement". And it is no

less good, has nothing devaluing, but is simply something other

than sport (in my sense).

A relationship with an other human being can also

be taken up across temporal and local boundaries inwardly, in

the imagination, with a human being in a completely

different place, even with a human being (as a role model or

competitor) who is no longer alive. Such an indirect, inner

relationship is the basis of the record principle in sport, according

to which the aim is to outperform achievements which have already

been achieved at some point and about which there is a handed

down, credible, and traceable report (this is the original

meaning of the English word "record").

In my opinion, the "record principle" in sport is harmful and

expendable. In principle, in sport it is not the question of

providing a performance that has not been surpassed so far

(superlative), but rather a better one in concrete comparison

here and now than the competitors (comparative). The

fixation on the achievement of ever new top and best performances

(records) is not only a hazard for the athletes' health, it is

also generally not good for the society.

In the competition itself, in which the here and

now principle applies, the relationship is immediate: the

other people are known to me, close in time and space (and I to

them), the desired comparison takes place directly with them.

The establishment of a relationship with another person and the

associated intentions and goals are - as psychological processes

- not always easy to be recognised in the individual, concrete

external actions, sometimes not at all. In my opinion, however,

the intentions and goals are decisive for the relationship of the

people involved and thus for whether or not their actions are to

be located in the field of sport. Therefore the (social and)

psychological context has to be considered carefully.

An example: When I sprint to reach a bus, I don't

act sporty. The action of the sprint may be (almost) the same as

that of an athlete in training or competition, viewed from the

outside; but my sprint to the bus does not happen to me - at the

level of that action! - to enter into a (comparative)

relationship with other people. In sports training or

competition, however, I sprint to get myself - on the level of

this action! - to enter into a (comparative) relationship with

other people.

Perhaps the boundaries of meaning become even

clearer when I take the example just mentioned to extremes: If,

during the sprint to the bus, I saw another person sprinting to

the bus from the other side the same distance and if I somehow

agreed with him/her that we could both compare, compete, the who

of us reached the bus door earlier, then all the definition

elements for "sport" would be given: Out of this small everyday

situation we both would have made a small, fleeting situation of

"sport".

In many activities, which are colloquially and

broadly assigned to sport, the relationship element at the

activity level itself and / or the aim of comparison according to

rules is missing (see below!), for example in movement

training for the purpose of rehabilitation (so-called "health

sport"!), jogging (except as training for a competition),

juggling, dancing (except tournament dancing), fitness training

or "body building"; they are therefore not sporting activities

for me, even if people may live a different kind of relationship

(e.g. sociability) during or with this activity. The relationship

with (at least) one other person must be necessary for the

activity itself, lived in it and through it, and it must contain

the other elements of definition (intention of comparison, etc.)

if the activity is to belong to the field of activity "sport".

For me, the above-mentioned and many other activities belong

predominantly to the field of activity "culture of movement".

However, the boundaries are not rigid. One can - as

shown in the example (sprint to the bus door) and as can be seen

in the cultural history, e.g. of dancing and gymnastics - make a

lot of things into a sporting activity, convert into a

"sport".

"abilities": The differently

gifted people have or develop different possibilities for action

in different fields of activity, including sport. The term

"abilities" rather refers to general, comprehensive possibilities

of acting which can be based on talent, genetic "equipment",

constitution, practice and experience, e.g. being quick to react

or flexible or persevering or being able to assess a complex

situation quickly and correctly.

In the course of cultural history, the sometimes

considerable differences in the possibilities of acting by

different people - congenital or acquired - have led to different

classifications of competitors in the sense of a "fair"

comparison of the "art of movement" (see below!),

especially according to age, body weight, gender and type of

disability (in this historical order). Since each such

classification represents an (arbitrary) regulation (see

below!), it can and should be disputed. The fact that, for

example, there is no (even) classification according to body

length means that in some sports small people hardly have a

chance compared to large ones (and sometimes vice versa); I

consider this to be problematic; however, it can (also) be

regulated.

"skills": This term describes more

specific acting possibilities, smaller action elements, which can

be acquired / developed in particular through intensive practice

(training), e.g. safely handling dumbbells, jumping a somersault

or (while sailing) driving a fast turn / jibe.

At least in the past it was possible for (adult)

people to have certain movement abilities or skills of such a

high level due to their inherited trait and/or natural and

cultural living conditions alone that they were not only

competitive in sports without any additional special training

effort, but were also superior to people from other cultural

areas, e.g. the Ethiopian marathon runner Bikila Abebe 1960 in

Rome (at that time even barefoot) and still in 1964 in Tokyo (but

then with running shoes).

In general - also with Bikila Abebe, but in a

culturally different way - the development of sporting action

possibilities consists of a long process of learning, practicing,

training, mostly under guidance. This also has usually been the

case in earlier times and cultures.

But there were also "natural talents" who - only

apparently - "just like that" would have been competitive in the

"sports" developed by Europeans (and Americans). At the beginning

of the 20th century, German / European colonisers in today's

Rwanda, for example, were astonished to discover that there were

many young men in the "Watussi" tribe (today: Tutsi) who jumped

above heights that were far above the high jump "world record" of

that time. However, the young Tutsi did not acquire this ability

for a (sporting) competition, but as proof of their acquired

manhood. It

was a socially anchored form of movement culture.

In the "art of movement": Every

activity has a motor part, even if it may be small and hardly

perceptible from the outside. A designation of the field of

activity to be defined only with the term "movement" would

therefore not be very selective.

With the word "art" (of movement) I want to point

to a graded consideration of the quality of movement,

through which a differentiation from everyday movements in

particular becomes clear. Instead of "in the art of

movement" I could also say "in the skillful

movement". "Art origins in ability" - this saying (in German:

"Kunst kommt von Können") has been in my head with the word

(component) "art", and not possible aesthetic meanings of

art. The point at which the nature, extent and significance

of the (skillful) movement are sufficient to designate an

activity as sporting is not fixed, but remains open in this

definition; this can and must be discussed and argued about.

It must depend on the skillful

movement that must be at the centre of the activity. How many

calories are expended is not essential. The sentence "sport is

when you sweat and take a shower afterwards" remains a nice

definition joke.

So, for example, playing chess does not count as a

sport for me, because playing chess does not essentially

depend on abilities and skills in the field of movement art, but

on the mental-strategic and tactical activity. Chess players of

the highest skill levels need hardly move at all; they only have

to say "e2 - e4" and "e7 - e5" to each other etc. in order to

play (start) a game of chess according to all the rules of the

art (e.g. in correspondence chess). The fact that chess players

also put physical strain on themselves during their competition

games and therefore sometimes also undergo fitness training does

not change the fact that it is not essential for them to move

artfully. At tournaments they may get into sweat, but this

remains part of everyday physical strain, which can be better

endured with trained fitness. "Shuffling clogs" remains in the

area of everyday movements, is even basically dispensable and

certainly not to be settled in the area of movement art. Also

when "flashing" it does not depend substantially from the

movement. It is of course helpful to be able to get the

opponent's watch going as quickly as possible with concentrated

movement; however, the decisive factor remains the intellectual

performance to make the right draws.

By the way, only the so-called protection of

existence as a (founding) member of the German (meanwhile

"Olympic") Sports Federation prevents the German Chess Federation

from being excluded. Everyone involved is probably aware that

chess is not (a kind of) sport. Since the International Olympic

Committee (IOC) has even recognized bridge games as a sport as

well as chess, it has lost for me at the latest any credibility

as "guardian" of the idea of sport (even if I myself like to play

chess and bridge).

A somewhat different borderline case is "motor

sport", especially "automobile sport". Here it seems to depend to

a significant extent on the quality of the equipment that is

available to the drivers (similar to "equestrian sports", see

below). When Michael Schumacher, "record world champion" in

Formula 1, was almost never able to drive at the top again in the

season after his last title defence, because his (new) racer was

obviously worse than those of his competitors, it became apparent

that in "automobile sport" (at least in Formula 1) the device is

probably more important than the driver, who was (at that time)

still regarded by his competitors as the (actually) better one.

Because my understanding of sport depends on the art of human

movement, I don't count car racing among the sporting events.

It seems similarly questionable to me in dressage

and show jumping, where the class of the horse often determines

the comparison. Just think of the "miracle mare" Halla, who 1956

in Stockholm carried the injured and heavily sedated Hans

Günther Winkler to the finish line in the second round of

show jumping to win the gold medal without any faults, or of the

former "miracle horse" Totilas, who was supposed to guarantee his

new (dressage) rider Matthias Rath victory - as long as it was

healthy.

The sporting principle could be "saved" or

reestablished in such competitions, for example, if at least the

people qualified for a final fight (e.g. the last four) had to

prove themselves with all the foreign equipment or horses. By the

way, such a rule has already existed in the past for horse

riding.

In the flat race the respective horses are honestly

named as "winners", the (respective, changing) jockeys only in

second line; this is obviously not a kind of sport in the sense

of my definition, even if the operators and fans traditionally

(with nostalgic, obsolete "historical" reasons) attribute

themselves to sport. The fact that even the breeders or

respective owners of the horses are also celebrated as sporting

winners (wrongly, because they are really not active in the field

of skillful movement) points to the late feudal origins of this

social phenomenon, which in today's capitalist society continue

to be cultivated.

In discussions with me - of all me, a violinist and

viola player! - some people argue: Musicians have to practice the

highest art of movement with their instruments, they are in

relationship with other people, they strive for high performance

in organised comparisons, etc., in short: According to my

definition, making music with instruments is probably also a kind

of "sport". This is opposed - despite the correctness of the

individual statements - by the fact that movement for

instrumental musicians is a means for a purpose, that the sense

of playing an instrument or even singing does not consist in

(skillful) movement, but that movement when making music

serves to produce (melodious) sounds, no matter how

demanding, strenuous and sweaty this activity may be.

In sport, it is important to master a previously

agreed and regulated challenge through skillful movement(s) and

to be better than the competitors; the "leibliche"

(perhaps better than bodily!) art of movement is the

determining factor, what matters. The extent of physical movement

is not fixed.

Another area that is often disputed in discussions

with me is, for example, the question of whether or not (the

olympic "sport-") shooting is a sport, as I define it - except

shooting hunters, soldiers, policemen, etc., of course. The fact

that targeting requires to control movement with a tendency to

limit it as much as possible (especially in biathlon, when the

cross-country athletes struggle against their movements caused by

heavy breathing), seems to indicate that shooting does not fit

the definition. For me, however, it is a special art to

control the movement in a way to master it so skilfully,

that a promising situation is brought about, which one can use to

meet the target. The extent of the movement visible from the

outside is (when shooting and in principle) not what matters

here. Anyone who ever tried sport-shooting (with pistol or rifle)

will confirm this; when shooting at moving targets (trap) as well

as in archery, even the layman will probably be able to

understand this. A similar argument could also be made (and

refused) with regard to the "holding" and "standing" parts in

gymnastics or figure skating.

By the way, in the realm of shooting "sport", it

should be considered to generally replace the actually used

lethal guns by nonlethal ones, by new rules, or if necessary, by

law! This would meet the ethical commitment at the end of my

definition (see below!).

"compare": People with their

abilities and skills can and want to (apparently in almost all

cultures) compare themselves with other people in the field of

the art of movement as well, in order to determine the better in

different modes of activity, which have been and still are

developed culturally for the sake of better comparability

("sports"). This happens by its nature in the form of a

direct regulated comparison ("competition") in a certain

place at the same time (with or without witnesses and / or

referees).

Since the 19th century, also indirect

comparison systems have been developed which increasingly brought

more individuals or groups into competition with each other and

which were / are not designed for a selective, immediate

decision. To this end, people have developed various forms of

preliminary, challenge or qualification competitions, first of

all in the team sports (leagues, round matches, etc.), then also

in the individual sports. The forms of such comparisons

constitute the empirical richness of sport history. The motives

behind the individual people or teams involved or the social

groups supporting them, the significance of these comparisons for

them, are also interesting historical and current

circumstances.

The mere display of even the most highly developed

abilities and skills in the field of movement art (e.g. circus

artistry) is not a sporting activity for me, because (or insofar

as) here the comparative relationship to at least one other

person in this field of activity is missing or not

essential. There are many former (top) sportsmen and -women who

have switched to the show sector (e.g. figure skaters); according

to my understanding of the term, they change from "sport" to

"culture of movement". They perform their high art of movement

without primarily striving for comparisons with other people. One

can also compare specific artists with others, but the comparison

is then brought to them from the outside and does not essentially

lie in their own activity.

Since one's own acting is a necessary component of

my definition, all those who only incite other people to a

comparison in the field of movement art are not "sportsmen"

either, as e.g. the English "gentlemen" did in the late feudalist

resp. early capitalist period ("patronage sport"). They let their

servants or other (paid) people compete against each other (in

horse-racing, running, sailing etc.) and bet on the outcome

(hence "Wettkampf" in German!).

It may be irritating that it was precisely this

delegating of their actions ("sportsmanship") that was the

cultural-historical origin of the (early, English) term "sport".

Letting other people act for themselves is still occasionally a

historical remnant in today's "sport", for example when the

owners of large (and very expensive) sailing yachts are declared

regatta "winners" according to the rules on construction and

equipment, even if they were not on board at all. They are not

sportsmen for me (see above the remarks on horse racing!).

As an active member of their crew, they are of course.

"According to self-imposed or adopted

rules": Since sport is about voluntary activities as well as

about a comparison of movement abilities and skills, the people

in this field of activity must compound with or adopt (proven)

rules according to which the better, the winner of the

competition, is to be ascertained and determined. Without such an

agreement - for me of course on the basis of respect for one's

own life and that of others (see below!) - sport would

easily become a rampant, destructive struggle, war.

Incidentally, there is much to be said for the assumption that

the most deadly duel is a "predecessor" of sport, which has been

culturally "defused", "tamed" in the course of cultural

development by limiting through rules.

No matter how bizarre the agreed rules may seem,

how difficult to understand they can be for outsiders; as soon as

they are understood and accepted by all the actors involved, they

constitute for them their own (cultural) field of activity - in

other words: sport - in which the "victory" is also fought for

with rules-utilizing hardness.

The "fairness" often invoked in this context is

another term to be clarified which, in my opinion, is often

wrongly located in cultural history and, moreover, excessively

morally charged. For me, the core of fairness, not only for

cultural-historical reasons, is the regularity and the resulting

predictability, reliability, on the basis of which all those

involved gain security of action when they fight for victory (or

for material advantage in bartering; the English word "fair"

still means a togetherness, at which goods are exhibited and

exchanged, traded).

"on the basis of socially accepted ethical

values": I "slaved away" with this definition element,

and for a long time I was not completely satisfied. At first my

formulation was "without wanting to harm them or themselves". I

wanted to make it clear that I wanted to rule out any

intentional harm. In sports, carelessness and unfortunate

situations, "in the heat of the moment", can lead to harm;

that is ethically not a fundamental problem. The only important

thing is that there is no intention, no deliberate negligence, no

endorsing accepting. This should always be (self-) critically and

thoroughly examined and clarified, if necessary also by referees.

In the best case - and fortunately often - this succeeds by the

parties involved agreeing immediately afterwards (often without

words, with glances and gestures) and peacefully separating (for

example with a conciliatory handshake), in order to continue

fighting for success in the sporting competition unburdened after

this good clarification with rule-utilizing hardness.

In one of the many discussions about the concept of

sport, it has become clear to me that it is more general and

better to refer to (general) ethical values, and that the

addition "socially accepted" refers to the norms as culturally

dynamic, its constant change (hopefully in a good direction!)

makes clear, both within a certain society and in comparison of

different societies (see below the example

pankration!).

In general, it is true in (almost) all societies

that no one may intentionally harm another human being. This

applies in particular to the relationship of responsibility

adults (parents, trainers, etc.) have towards children and young

people. My earlier formulation, which expressly also addressed

self-damage, was particularly determined by the problem of

doping. Doping and other possible forms of self-damage are also

excluded by the new more general wording (as well as partly by

the reference to the sports-specific rules and regulations).

However, in this area there are unfortunately scandalous

repression and cover-up efforts as well as too weak control and

sanction possibilities.

In the field of sport, too, the general ethical

norms naturally apply first and foremost; the "rules" specially

agreed for each kind of sport represent further, supplementary

norms. Regularity is a necessary, but not sufficient determining

factor for sport; it only by itself does not establish an ethical

standard (see below the remarks on boxing) as it is

generally accepted or demanded by society.

In questions of sport ethics, it is dubious for me

and necessary to discuss whether the legal principle "lex

specialis derogat legi generali" also applies here, i.e.

whether a special sports rule precedes the general ethical rules

and undermines them. One example is the current boxing rules,

according to which it is "allowed" to (severely) injure one's

opponent (see below!). I think that this legal principle

should not apply in sport. However, this question should be

discussed intensively and responsibly in general and in each

individual case.

A positive example of the primacy of general

ethical standards over rules based solely on the sport is in

sailing - similar to the road traffic regulations, by the way -

the requirement to perform a "manoeuvre of the last moment" as

far as possible, even if according to the right of way rules one

would have the right to maintain one's course. The sense is

obvious, not to harm anyone, not even the ships. Whoever does not

follow this general, superordinate rule (without necessity) will

be made co-responsible and possibly disqualified for the

following collision during regatta sailing despite his "right of

way".

Depending on the sense and tradition of a (kind of)

sport, sport specific rules are sometimes ethically problematic,

especially in combat and risk sports. Boxing, for example, is an

ethical border area for me, because according to the

current rules, it is part of the meaning of boxing to tend

to make the opponent by rule-utilizing toughness incapable of

fighting and thus also to accept serious consequences for the

health (up to death) for oneself and the opponent. Numerous

deaths directly "in the ring" and even more cases of severe

damage to the health of boxers are sufficient for me not to

regard boxing in its current form as a (kind of)

sport.

The rules could be changed by the (international)

boxing federations in such a way that these severe circumstances

or consequences would be decisively alleviated, for example by

changing the design of the boxing gloves. Only after the rules

have fundamentally "defused" would we be able to recommend our

children with a good conscience that they could take part in this

potentially very interesting sport. The half-hearted regulations

of a (controversial in its effectiveness) head protection have

obviously not decisively reduced the health risk.

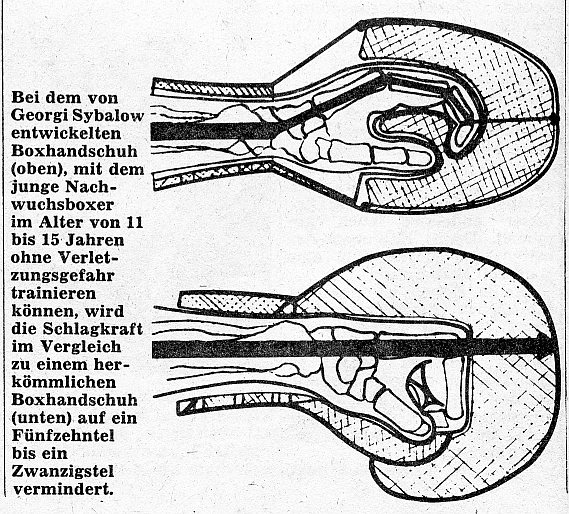

About forty years ago, the USSR boxing organisation

made a completely repressed, in my opinion revolutionary attempt

to reduce the kinetic energy (and thus the effect) of straight

shots to estimated 5 percent by changing the position of the

hands in new boxing gloves (in the sketch above). For this

purpose, boxing gloves were proposed in which the middle hand was

slightly angled upwards and the finger joints were held slightly

curved in an open position in the glove (source:

report in the German daily newspaper "Unsere Zeit" (uz) of 09.

29. 1978).

. .

This change of the rules would have considerably

reduced the health risks to boxers caused by numerous minor

concussions. Boxing would have been changed in the direction of

modern fencing, in which since a long time only symbolic

hits, light touches, have been achieved, which are determined

with high technical effort. Unfortunately, this proposal has not

been taken up. One may therefore assume that the majority of the

boxing officials (even in the amateur and youth sector, which was

"only" concerned at that time!) was (and still is) interested in

preserving the questionable "attraction" of boxing as a possible

(considerable) health hazard.

Historically, in my opinion, the ethical limit of

the prohibition of foreign or self-damage has been clearly

crossed from the outset in Roman gladiatorism, even if the

opponents were volunteers (which certainly sometimes happened).

In my opinion, gladiatorism should therefore not be dealt with in

representations of sport history; for I cannot count it as part

of the culture of movement either.

Also in some so-called "high-risk sports" the limit

of self-damage is in my opinion reached or exceeded.

The concrete demarcation can and must also be

argued about in this part of my definition in any case; everyone

will want to draw the demarcation somewhere else, but should -

especially as a scientist - disclose his (her) motives and

reasons for it.

|